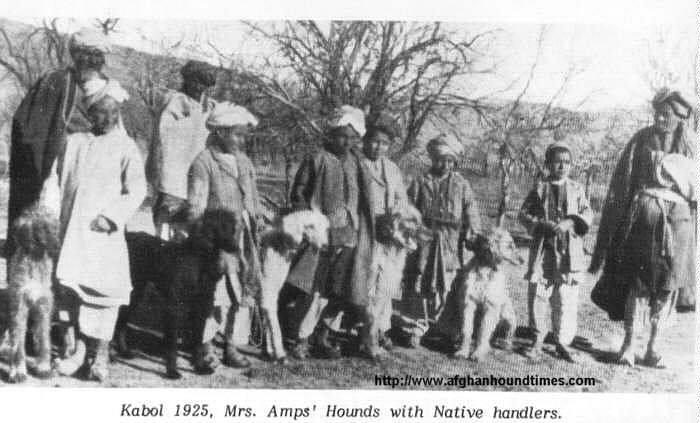

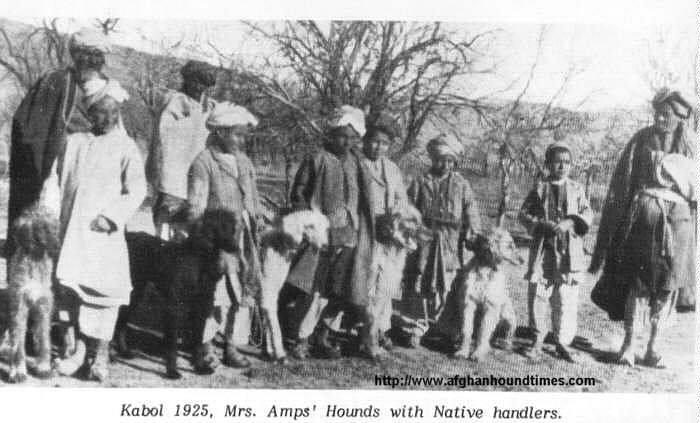

THE HOUND IN AFGHANISTAN

(Mrs Mary Amps 1932)

The following article is an abridged version of a section on Afghan hounds written by Mary Amps

for Croxton Smith's 1932 book - " Hounds and Dogs - Their Training and Working", This article

was Published in The Longsdale Library Of

Sports, Games and Pastime Vol XIII: 1932

Until comparatively recently almost as little was known about the Afghan hound

as of his strange, inhospitable country, ringed by inaccessible mountains.

Shortly after the Afghan War of 1919 a British Minister and Legation were

appointed to Kabul, and the country then became better known to Europeans.

When out riding or shooting it was impossible not to notice the well-bred and

beautiful hounds owned by some of the shikaris. They were a great contrast to

the smooth coated "long-dogs" one is used to on the Indian Frontier, In

conformation rather like the English Greyhound, the Afghan hound is sturdy and

more compactly built, carrying a thick silky coat which enables him to

withstand the cold of the Afghan winter, for at an average height of 6,000 feet

the temperature for three months of the year is often below zero and the snow

lies in drifts 10 to 15 feet deep. The texture of this coat is a fine silky

wool, which is unlike that of any other dog. The distribution of the coat is

another characteristic of the breed: the chest, forelegs and the hindquarters

are heavily coated with long, rope-like cords leaving the saddle smooth with a

short and much darker hair, usually coarser in texture.

The muzzle is clean and dark and an upstanding topknot of long, silky hair

crowns the head which has very little stop. The long graceful ears are heavily

feathered. The whole effect is rather that of a wig in the time of Charles the

Second. They have large compact feet and a thin, sparsely coated tail carried

jauntily upward, terminating in a smaller curve. The bitch is usually smaller

and carries less coat than the dog.

The expression is kind, intelligent and aloof, and this air of complete

aloofness from their surroundings is very noticeable on the show bench. They

have charming manners and are essentially a "one-man-dog". I do not advise

anyone to keep Afghan hounds in kennels. They are used to living with man, and

when deprived of his company they are unhappy and half-developed and tend to

become disobedient. It seems necessary to them to have a master or mistress to

whom they can give their dignified devotion. They are good house dogs,

marvelously kind and gentle with children.

Information as to the history of the breed is slight. The Afghans believe they

are the dogs taken into the Ark by Noah, and point to the rock carvings of

hounds in the caves of Balkh, in northern Afghanistan, as definite confirmation

in this belief. The Hon. Mountstuart Elphinstone in 1815 writes in his "Account

of the Kingdom of Cabul and its Dependencies", "The Greyhounds of Afghanistan

are excellent."

In 1857 Major Harry Lumsdem of the Queen's Own Corps Of Guides, who was on a

mission to Kabul when the Indian Mutiny broke out, mentions Afghan hounds in

his diary, and was apparently able to do a certain amount of hunting there in

spite of the difficulties and suspicion he encountered. General Sir Francis

Younghusband and Major-General Dunsterville (the "Stalky" of Rudyard Kipling's

famous book) also mention keeping Afghan hounds at Maidan, the headquarters of

the Guides Regiment in their young days.(Ed Note, Maidan Province is S.W of and

immediately adjacent to Kabul Province).

There is usually considerable difficulty in obtaining information about anything

in Afghanistan. Centuries of bloodshed and oppression have made the inhabitants

of the "God-given country" more than usually secretive about their own ways.

We have sometimes visited villages where really good hounds were known to

exist, only to be met with polite and blank assurance that none were there.

When later on we went again with an Afghan gentleman the hounds were produced

almost at once. They part with them with the utmost reluctance. Money alone is

not sufficient to buy a really good bitch. Packs of Afghan hounds are kept by

the Governors and Maliks of the towns and districts.

Monsieur Hackin, the well-known French archaeologist and Buddhist authority of

the Guimet Museum, Paris, who had exceptional opportunities of traveling in

the lesser known parts of Afghanistan, told us of a pack of chinchilla hounds,

grey with black points, kept by a Governor of a district near the Oxus, if

hounds of any other colour are born, they are thrown out of the pack, and,

being greatly sought after by the Afghan shikaris, find their way as far south

as Ghazni and Kabul. Khan Of Ghazni, a fine, honey-fawn coloured hound, imported

into this country in 1925, came from this pack. I had one perfect chinchilla

bitch sired by him and I understand that a son of his, Mustavi Of Ghazni, the

property of Mrs. Cooper, also sired a number of chinchilla hounds.

The Afghan as a rule is a keen sportsman and most of the shikaris in the

country districts keep a few hounds. A lot of nonsense has been written about

the bitches being kept solely to guard the women in the harems. The Afghan hound

in his own country works for his living and that of his masters, and the same

rule applies to the bitch. They are both trained to hunt deer and wolves, and

also to course hares and foxes; in fact anything that will bring grist to their

owner's mill. Incidentally, they act as watch dogs also. When in Kabul we

found that as night fell the latest recruit to our household became uneasy and

anxious to go beyond the boundary of the Legation walls in order to hunt. We

came to the conclusion that in many cases they were let loose to hunt for

themselves at night time. However, after a few days good feeding, they usually

settled down quietly after the evening meal.

A constant source of trouble to use in Kabul after purchasing an Afghan hound

was the attempts often made to steal back the dogs. They sometimes succeeded in

spite of a ten-foot wall and the armed Afghan guards at each entrance. This was

very difficult to circumvent as the dogs were always hidden away in the

previous owners houses in the high-walled Afghan villages where no European

may penetrate. We found the dogs remarkably good tempered among themselves and

less inclined to resent a newcomer of their own kind than most English breeds.

This was a blessing as we often had twenty to thirty hounds at a time.

We used to ride out over Chardeh Plain in the early mornings with a couple of

mounted orderlies to whip-in. To see the whole pack streaming along with the

galloping horses in the early morning sunlight with the keen air blowing from

the snows of the distant Hindu Kush was a sight and experience never to be

forgotten and I fear never to be enjoyed again. England is too small and too

domesticated! In Afghanistan the hounds never show the slightest tendency to

chase the innumerable sheep, cattle, camels and donkeys scattered over the

countryside. They are pretty thoroughly trained from puppyhood what to hunt and

what to leave alone.

One of the oldest forms of hunting, which is often portrayed in old Persian and

Mogul manuscripts, is still carried on in the remoter parts of Afghanistan.

The quarry, a small very swift deer called the Abu Dashti, is hunted by Afghan

hounds with the aid of hawks. The birds used are of two kinds, the yellow-eyed

and the black-eyed, usually distinguished in European countries as the long-

winged and the short-winged hawks. The female of both varieties is the larger

and more valuable bird. The black-eyed birds known as Chahughs, which build on

the low mounds in the Balkh district, are most commonly used. They are never

unhooded except to fly at game and they spot the quarry with incredible

quickness at enormous distances, even in the sudden glare of the tropical

sun.

The young birds and Afghan puppies are kept together, the young hounds being

fed on the flesh of deer whenever possible. The food of young hawks is placed

each day between the horns of a stuffed deer, later a string is attached to the

head and is drawn across the floor, the young bird flapping after it. As soon

as they are able to fly they are released and called to this lure. As the

training progresses they are flown at a young kid and when they seize it the

animal is killed and they are fed on the flesh. When fully-grown the hounds are

loosed after a fawn and the hawks flown at it.

The training completed, hawks and hounds are taken to the hills. Immediately

the deer is spotted the birds are unhooded and released and they descend above

the head of the unfortunate beast, and, by flapping about it, impedes its

progress sufficiently to enable the hounds to overtake it and pull it down. The

Abu Dashti or Chinkara, as it is known in India, is so swift that it is said

that "the day a Chinkara is born, a man may catch it: the second day a swift

hound; but the third, no one but Allah".

It is interesting to see quite young puppies whose parents and grandparents have

been born and reared in the country climb to a point of vantage in order to

watch the flight of a large bird. The Afghan hound possesses very keen vision

and hunts by sight.

Two Afghan hound were exhibited at a show of foreign dogs at the Royal Aquarium

in 1895. They formed the subject of an article in the "Field" by the late W B

Tegetmeir and were sketched by Arthur Wardle. The reproduction of one that I

have before me shows a fie upstanding hound, typical in every way except that

he has no topknot, the occiput being smooth. When Captain Barff's Zardin was

bought to this country in 1907 he caused a sensation. He was a magnificent

specimen, heavily coated and rather larger than the average. His appearance at

the Kennel Club Show created enormous interest and he was taken to Buckingham

Palace at the request of her late Majesty, Queen Alexandra

Mr. Whitbread's Shahzada was another early arrival and it is still to be seen in

one of the glass cases in the Natural History Museum, South Kensington. The

breed is now well established in this country, Holland and France and is

growing in popularity every year. The Afghan hound possesses in full those two

qualities so rarely seen together, brains and beauty.

I would like to add a note of warning. Many of our breeders and judges today

clamour for size, for bigger hounds at any cost. The Afghan hound, is, or

should be, of the Greyhound type but sturdy, compact and capable of endurance

in order to enable him to hunt all day over the barren, rock, precipitous

mountains of his own land. The struggle for height so often results in

coarseness or weediness at the expense of quality. The origin of the Afghan hound

is lost in the mists of antiquity but his Afghan master has kept the breed

unaltered for some two thousand years. It seems a pity to alter it now for the

English show bench.

(Mrs. Mary Amps 1932)

See also

Hounds and Dogs - Their Training and Working" by Croxton Smith 1932 (4mb PDF)

Ghazni Afghan Hounds Section. Steve Tillotson 2013

Lieut-Colonel L.W. Amps and Mrs Mary Amps By Steve Tillotson and Lyall Payne Nov 2013

Lt. Amps and Mary Amps "Nice Buddha; nice set of wheels" By Llewellyn Morgan (Oxford, England Sep 2013

The Hound In Afghanistan, Mary Amps, 1932

The Land Of The Afghan Hound, Mary Amps, 1930

Mrs Amps and her famous Afghan Hounds By Phyllis Robson 1930

Robert Leighton on Mrs Amps Ghazni 1926

Afghan Hounds In India, Steve Tillotson, 2012

Afghan Controversy What is the correct type? Amps and Bell Murray

Bill Hall Meeting/Interview with Major-Genl Amps 1970's

Susan (Sirdar of Ghazni daughter)- Identity Revealed. Lyall Payne and Steve Tillotson Sept 2015

Early Afghan Hounds Section

The Origins Section

Library Of Articles/Main Menu Toolbar

Whats New Page

|