(Afghan Hound Database and Breed Information Exchange)

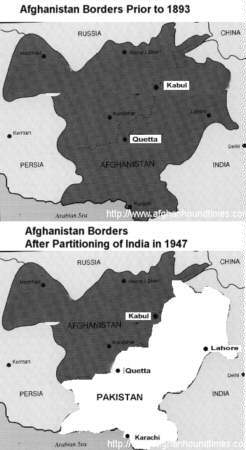

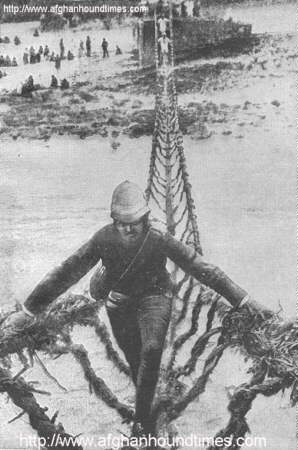

(Author Steve Tillotson, June 2013) The borders between Afghanistan and its eastern neighbours India/Pakistan have been the subject of controversy between all three countries since they were drawn up and imposed by the British, starting back in the late 1800.s. Firstly there was the "Durand Line" or border, drawn up by Henry Mortimer Durand, the Foreign Secretary of British India in 1893. The Durand Line serves to this day as the western Border between Pakistan and Afghanistan but it is unrecognized as such by Afghanistan. In 1947 the British granted India independence and this involved the "partitioning of India" on boundaries again drawn up by the British. Just prior to the partitioning of India took place, the British acceded control of Baluchistan (a large south eastern Province of Afghanistan) to its ruler the Khan of Kalat, the fact of independence being reported by the New York Times on August 12 1947 who next day published a map showing the independent sovereign state. Pakistan invaded Baluchistan in April 1948 and imprisoned all members of the Kalat assembly and Baluchistan eventually became a part of Pakistan. You can see the shift in boundaries in the graphic below  The British held to the border ("Durand Line") that they had previously defined in 1893 as that line being the border between Afghanistan and the new country of Pakistan. Simultaneously the borders between the new country of Pakistan and India were agreed (with some dispute over Kashmir in the north, such dispute being the subject of ongoing political and military conflict between Pakistan and India to this day). Britain achieved its several objectives - Its withdrawl from India and granting India independence, forced upon it by the protesting Indian populace, the partitioning of India into two separate countries (Pakistan and India) and, importantly by situating the new country of Pakistan between Afghanistan and India, Britain achieved its strategic objective of establishing a "buffer zone" between Russia and India. That buffer zone encompassing what was left of Afghanistan and the new Pakistan. Important cities such as Quetta, Karachi and Lahore which were originally within the borders of Afghanistan became part of the new Pakistan. In the long history of the British military presence in Afghanistan throughout the 1800's, the British occupied and controlled territory on both sides of the country. Their motivation was to protect their "Jewel In The Crown" (India, which was a source of great wealth for the British Empire) from possible intrusion by Russia and the potential threat to Britains interests in India. On the the western side the British were particularly concerned with controlling Herat and surrounding area which borders Persia (now called Iran). The British considered Herat as "The Key To India" and occupied this territory to counter a Persian/Russian alliance (that alliance eventually disolved mid century) that could have enabled the Russians to enter Afghanistan, then march east across country and enter India and threaten the British interests there. The other possible route that concerned Britain was an invasion via the North of Afghanistan via the old Afghan Empire ("Durani Empire"), then east into India. Ranjit Singh, a Punjabi (from the Punjab region in India, and leader of the Sikhs) expanded the Sikh empire that started in the Punjab and extended westward, to include Kashmir in north Afghanistan and as far west as Kabul (Afghanistan). In the process he drove the Afghans increasingly west which suited the British as they believed that the then Afghan ruler (Dost Mohammed Khan) was conspiring with Russia. Ranjit Singh had a very well trained and equipped army, and when allied with the British the resultant combination of their strengths would likely disuade the Russians from attempting a route into India via northern Afghanistan. Relevent to any discussion on Afghanistan of this era are the difficulties of travel. Consider these two diary notes by Colonel Algernon Durand (British agent at Gilgit 1889-1894 ) published his book - "The Making of a Frontier (1899)". (Ed Note; For the very observent amongst you who picked up on that name "Durand" this is a different person and not to be confused with Henry Mortimer Durand, the Foreign Secretary of British India). The Colonel was the British agent at Gilgit 1889-1894 and wrote in his book about his experiences in Chitral in the Indus Valley and of the difficulties in moving around that terrain. Consider these three reports - (1) During an earlier tour of duty, the Colonel wrote - "Crossing a mile above Chalt the rope bridge over the Hunza river, which seemed the longest and steepest we had yet crossed, though that over the Gilgit river had a span of three hundred and sixty feet, we found ourselves in Nagar territory, the first Europeans who had ever penetrated its mysterious wilds. The bridge was a new one, fortunately for us, for they are very unsafe when old, and should be renewed annually. This involves a good deal of labour, as nine cables of twisted birch twigs of the necessary length, in this case some four hundred and fifty feet, have to be prepared. The people therefore often put off the work and chance the bridge lasting, and I have seen bridges three and four years old in use. This is horribly dangerous; the birch twigs dry and perish, and the ropes break suddenly. As a rule they do not go all together, and I have seen a bridge in use consisting only of the foot rope and one side rope, and have crossed them when the connecting ropes were broken and useless, but I never did so willingly, for we had a terrible lesson. A native officer and half a dozen men had been sent on from Gilgit ahead of us to try the bridges, and to arrange for necessary repairs. Coming to one bridge they tried it carefully, going over one at a time, and examining the anchorage and ropes. Thinking all was sound they foolishly returned in a body, crossing, of course, one behind the other. As the leading man got well up the slope towards the timber anchorage, followed by five others, the ropes drew or broke, and the whole party were dashed into the water. Two men, entangled in the ropes, were washed ashore on the bank they had started from, for the anchorages on the far side fortunately held, and the ropes swung across the stream and ashore, but the other unfortunates, caught in the awful torrent, were swept away and instantly drowned. Only one body was recovered, and that forty miles down stream.  (2) During a later tour of duty, the Colonel wrote - "There were many changes since I had first come up to Gilgit. A ten-foot mule road now ran through all the way from Kashmir, only a few bad cliffs were still being worked on, good bridges existed over the Kishengunga and Astor rivers, and the Indus bridge, a wire-rope suspension bridge, was being rapidly constructed. Aylmer, who to my great regret had been transferred elsewhere, had before leaving built a temporary four-foot wide suspension bridge of telegraph wire over the Indus, just below the site of the permanent structure, which was of the greatest assistance, and for the first time in the history of the mighty river its upper reaches had been spanned by a bridge over which men, if they dared, could ride across, also which laden baggage animals could pass. I found the whole road covered with long trains of properly organised transport, and, mirabile dictu, on arrival in Gilgit, eighteen months' supply for the troops in hand. The change was startling and welcome. (3) The march was the worst on the whole road. Running along the last spur between the Indus and the Astor river the path struck the watershed at the height of ten thousand feet, and then dropped down the Hattu Pir six thousand feet in about five miles to Ramghat, or Shaitan Nara, the "devil's bridge," as it was more appropriately called, until the Maharaja piously renamed it. It is impossible to exaggerate the vileness of this portion of the road; it plunged down over a thousand feet of tumbled rock, in steps from six inches to two feet deep; then for a mile it ran ankle-deep in loose sand filled with sharp-edged stones; it crossed shingle slopes which gave at every step; it passed by a shelf six inches wide across the face of a precipice; in fact it concentrated into those five miles every horror which it would be possible to conceive of a road in the worst nightmare. The culminating point was that, for the whole way from top to bottom, there was not a drop of water to be found on it, not an atom of shade. With coolies in the hot weather the only way to tackle the ascent was by marching at night and sending on water half way for them; the descent we managed fairly comfortably by starting at from two to four in the morning. The road was so execrable that ponies which had made the trip once from Astor to Bunji were always considered unfit for further work without a fortnight's rest and good grazing. The Hattu Pir was a Golgotha; the whole six thousand feet was strewn with the carcasses of expended baggage animals, and in more than one place did we find a heap of human bones. The following comment was taken from the book "Caravan Journeys and Wanderings in Persia, Afghanistan, Turkistan and Beloochistan by J.P. Ferrier. 1856". Mr Ferrier was a French military person with extensive knowledge of Central Asia which he had journeyed through on many occasions. In the preface to his book the editor writes -- "There is probably no part of the world, not excepting the interior of Africa, which is so dangerous and inaccessible to the European traveller as Afghanistan and the countries of Central Asia" (c) Steve Tillotson June 2013 Related content Life in Afghanistan 1878 (a letter to home) Origin of the Afghan hound Early Afghan hounds |